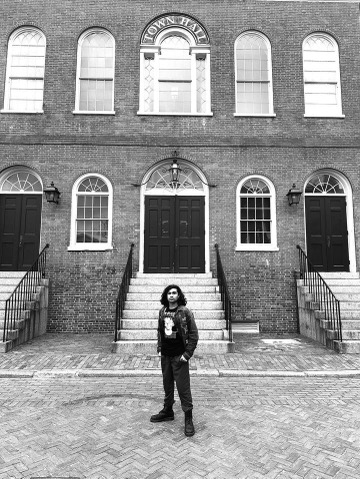

Boston, MA — For many Asian Americans, such as myself, the feeling of belonging is a commodity that is often deficient. Living in a country that can feel foreign, estranged, or even directly hostile, members of the BIPOC community at large find solace in countercultural movements. These communities in general, grant a voice to the unheard, a platform to express discontent and to purge oneself of the resentment held against a suppressive status quo. There is no better example of this type of community than punk.

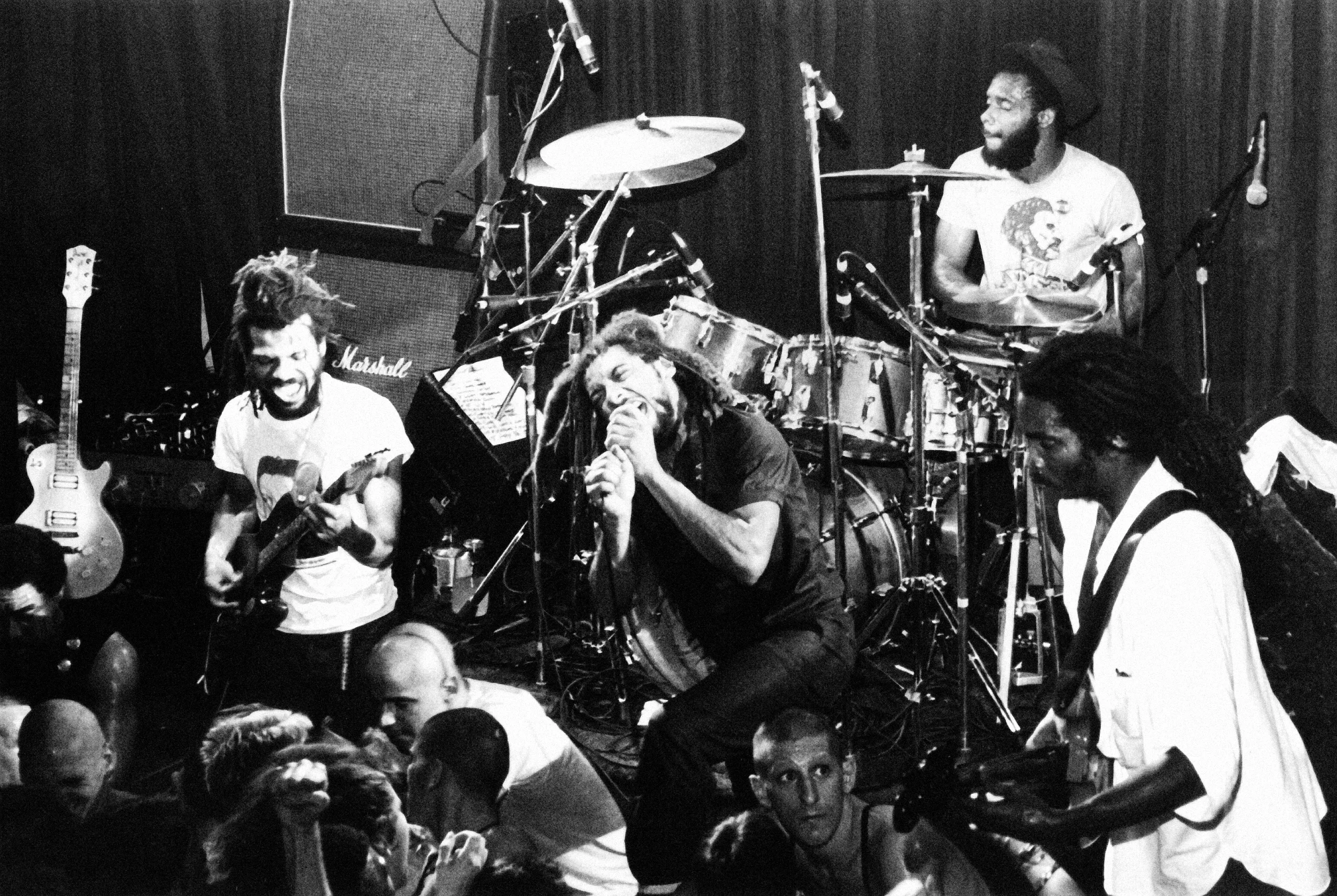

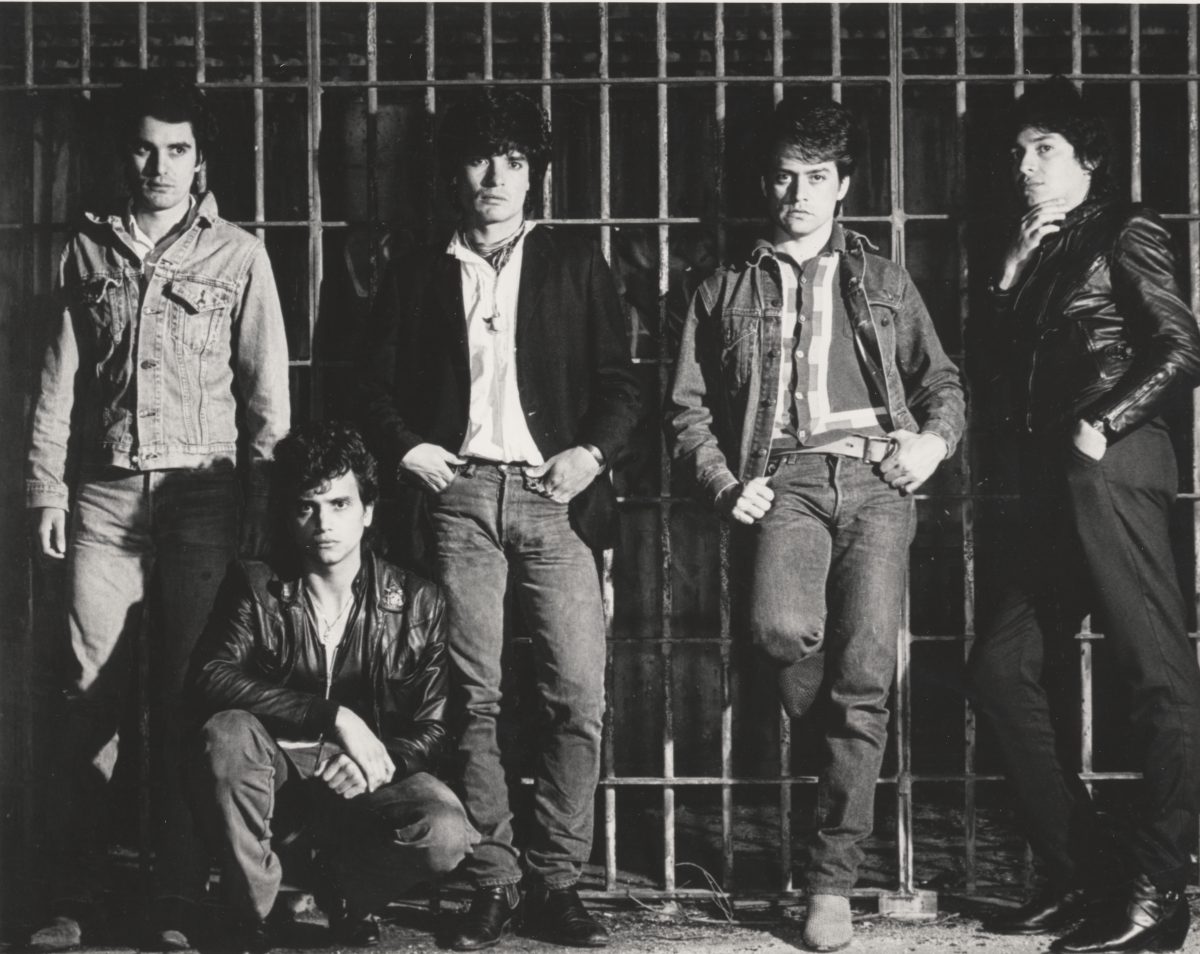

Emerging from the youth anti-establishment current of the 1970s, punk is aggressive, fast-paced, and politically charged. Under its rough exterior, punk is inextricably linked with ideas of acceptance, anti-bigotry, and leftist activism, appealing to marginalized communities of all types. Despite being a dominantly white subculture in the early days (and in some cases even today, albeit to a lesser degree), punk has been deeply linked with the BIPOC community from the beginning. Exemplifying the aggressive characteristics of punk rock, the all-black band Bad Brains pioneered hardcore as a subgenre.

Before more popular punk bands such as The Clash or The Ramones, the black trio called Death developed a hard rock sound that would prelude more traditional punk rock. As the genre developed, more marginalized communities began to find refuge in it. During the 80s, the queercore movement appeared, intertwining LGBTQ+ activism and punk. During the 90s, the riot grrrl movement combined the genre with feminism. Despite their appearance, punk shows are welcoming events. Often held in tight-knit, DIY venues, the sense of community is strong. The spaces are non-judgmental, providing something of a haven to those who feel unaccepted otherwise. The violent beats, performed out of passion, provide a platform for self-expression.

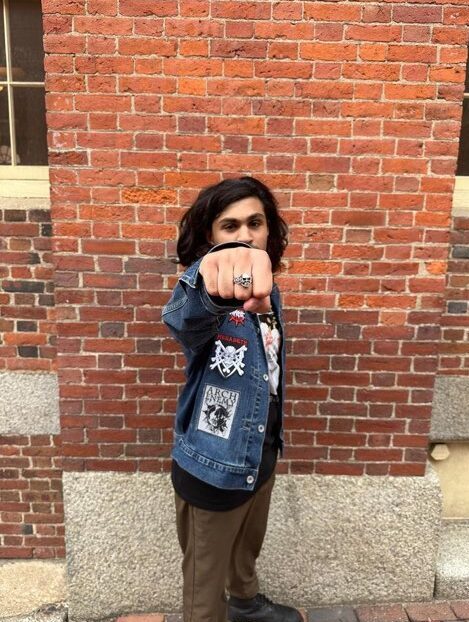

I found my own voice through playing this aggressive form of music. While being an outlet for my vexation, it’s simultaneously a genuinely enjoyable genre to write and perform. The ostensibly painful, harsh vocals are an expression of emotion that, contextually, can surpass more traditional vocal styles. Energetic, fast paced guitar riffs engage both mind and body, requiring precision and stamina.

As my fingers fly across the guitar’s neck, I release all the complex emotions involved, simultaneously allowing myself to experience them in their purest form. Indeed, punk allows many other BIPOC individuals and me who have been ostracized, targeted, and stereotyped to reclaim the voice and sense of belonging that we were denied.

Ethan Dang, the frontman of Massachusetts hardcore punk band Silent-Spring shares similar experiences “I feel that every marginalized group (beyond just race) has something to relate to the messages given in hardcore about grounding yourself and having you and your friends’ voices heard.”

“I had always been a really angry kid, being raised with my two siblings and a single mom on welfare. I had no place else to vent the things that had happened to me and my family – as a kid I had no other direction. Between The Things We Carry and seeing Converge in 2019 at Hardcore Stadium, I really felt like I was being given a power that I had nowhere else at the time just listening to the art of another set of people,” he said.

Too many marginalized communities lack a sense of belonging in America. Despite its mainstream image, punk is one countercultural movement that provides it, and as such has become an incredibly diverse community.

Ayaan Kazmi is a Boston-based writer/contributor at Maheen The Globe (MTG) a Seattle-based media outlet and independent production house covering global stories and perspectives. He covers beats race and music. His email is [email protected]

Ayaan Kazmi is a Boston-based writer/contributor at Maheen The Globe (MTG) a Seattle-based media outlet and independent production house covering global stories and perspectives. He covers beats race and music. His email is [email protected]